“There’s emerging evidence that links poor sleep to the development of dementia – particularly Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr Irene Szollosi.

People with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) often experience fragmented sleep and low oxygen levels (hypoxaemia). In the short term, this leads to poor sleep quality and daytime fatigue. However, if left untreated, OSA can contribute to a range of long-term health issues. Its full impact is not yet completely understood and is currently being investigated by researchers at The Prince Charles Hospital’s Sleep Disorders Centre.

“We already know that sleep apnoea affects cognitive function. If you’ve ever had a poor night’s sleep, you’ll know how it impairs memory, concentration, and reaction time,” said Dr Irene Szollosi. “But untreated sleep apnoea may also have longer-term consequences, potentially increasing the risk of developing dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.”

The researchers are working to distinguish between the cognitive effects caused by sleepiness and those caused by neurological damage from hypoxaemia and frequent sleep disruptions.

“We know that not everyone with OSA feels sleepy or notices cognitive issues, but a recent data analysis revealed a significant portion of these patients do show signs of cognitive impairment,” said PhD candidate Thomas Georgeson.

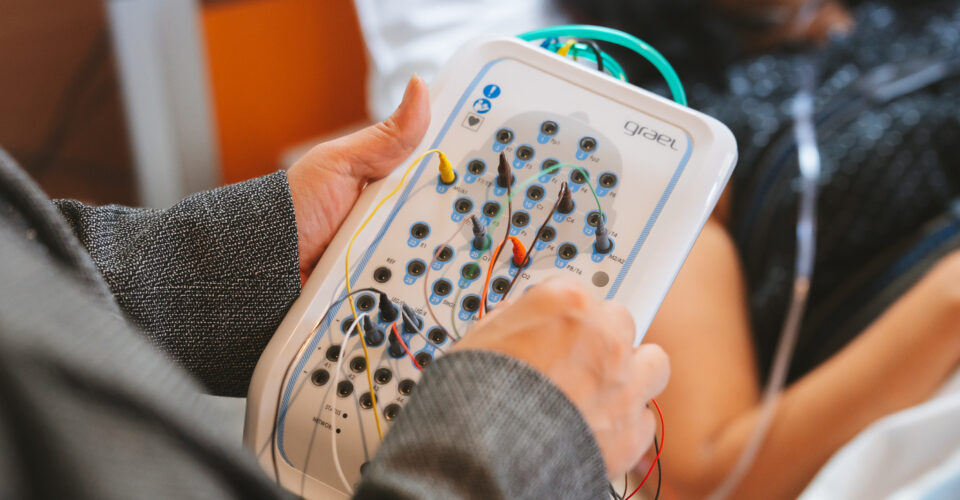

Mr Georgeson led a study titled Sleep Fragmentation and Hypoxaemia as Key Indicators of Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnoea, which used the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R) – a brief cognitive screening tool – to assess cognitive impairment in older individuals with OSA. The researchers analysed cross-sectional datasets from 89 adults aged 50–85. Results showed that 36% of participants were cognitively impaired (ACE-R score ≤88). The analysis identified a clear association between cognitive impairment and both sleep fragmentation and hypoxaemia, but not daytime sleepiness.

A follow-up study revealed that ACE-R scores improved with consistent use of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) therapy.

“Our findings show that regular use of CPAP therapy results in a small but meaningful improvement in ACE-R scores, especially in memory-related tasks,” Mr Georgeson explained.

Although cognitive function isn’t routinely measured in sleep clinics due to the time involved, Dr Szollosi emphasized the clinical value of using simpler tools like the ACE-R. Demonstrating both the negative impact of OSA and the cognitive improvement with CPAP using a brief test strengthens its utility in real-world settings.

“There’s been a significant gap in how we assess cognitive function in clinical sleep labs. We still don’t fully understand how OSA affects cognition or how quickly these issues resolve with treatment,” Dr Szollosi said. “There’s also a lack of research into practical outcome metrics focused on cognition for this patient group.”

She noted that the research supports the potential for simplified cognitive tools like the ACE-R to be used more routinely in clinical practice.

“Tom’s work gives us confidence that brief cognitive assessments can be both valid and clinically useful,” she said. “While the field is progressing rapidly, we still need to develop the right tools to evaluate both the short- and long-term effects of OSA, and to understand how effectively CPAP mitigates the risk of cognitive decline.”

Dr Szollosi added, “We know CPAP can reverse some cognitive impairment caused by OSA, but we also want to investigate whether any residual effects after treatment might predict future dementia.”